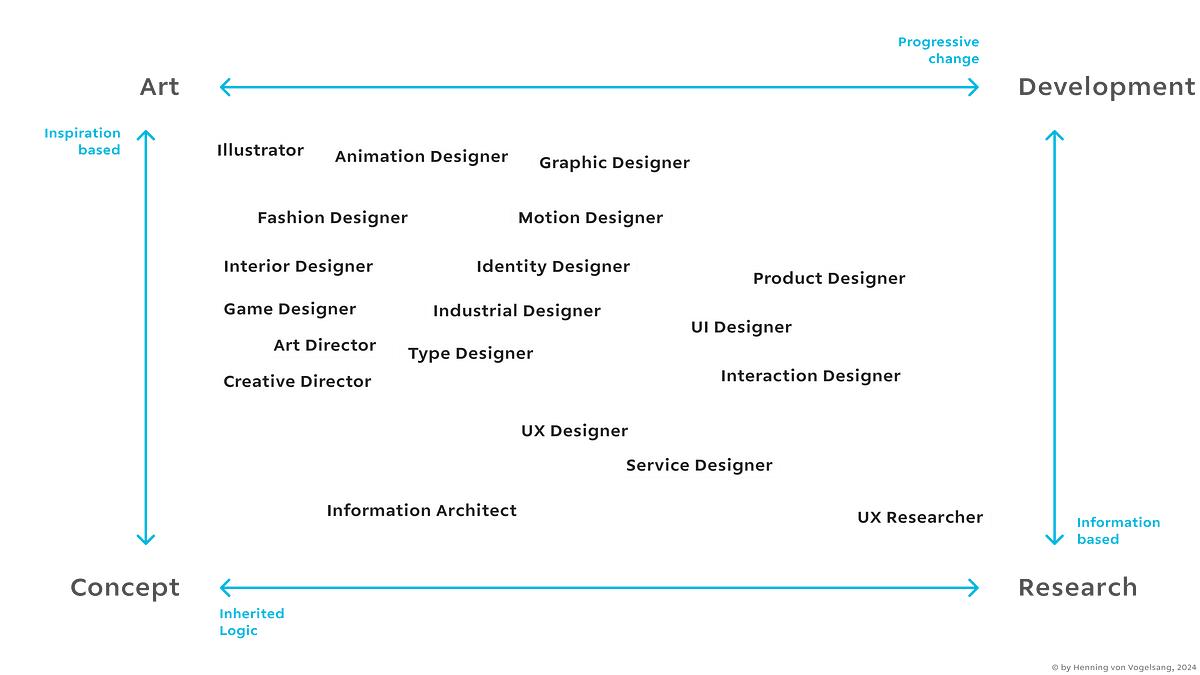

The Tension Field of Design

There’s a tension field between art, concept, development and research.

My sister’s husband is an engineer. The professionals working on the Chinese Lunar Exploration Programme are also engineers. So are their colleagues at ESA and NASA. A lot of my colleagues at the IT company I worked for are also called engineers.

Aside of the common naming, their professions couldn’t be more different.

My sister’s partner is an underground construction engineer. The people working on space projects are computer science engineers, robotics engineers, propulsion systems engineers, avionics engineers, mechanical engineers, and so on. My colleagues at the IT company are back-end, front-end engineers or system feature architect engineers.

It’s not uncommon to collect professional diversity in unifying name groups. A doctor can have a PhD in general medicine, psychology or anthropology, archaeology, law history, English literature, bio chemistry, astronomy or philosophy and so on. What teachers, lecturers and professors have in common with one and another is an underlying theme: they transmit knowledge and accompany students on their path of education.

It’s fair to say that the design and UX fields have slowly expanded over the last 40 years. From early beginnings and research and development to today’s insights and processes, we’ve learned a lot, and it would seem this would lead to a sharper, more concise image of what design in technology means today. But the opposite is our impression; the diversity and specialisation has seemingly led to more confusion.

Pragmatism or complication

Jakob Nielsen recently highlighted what he calls a “UX Vocabulary Inflation”, a literal dilution of meaning and clarity in the design fields. His main focus is directed towards the UX specialists, or UX practitioners fields. He lists the stepping stones of achievements in the history of User Experience and points out that these changing ideas also had an influence on the naming of associated professions. What Nielsen doesn’t like is the current trend of dilution and confusion that leads to insecurities and misunderstandings.

Nielsen is not alone: In his article “How to recruit a UX leader with the X factor”, Dr. Philip Hodgson also mentions the extensive confusion resulting from the colourful variety of names in the UX fields.

Recently I read a thread on X (Twitter) where they were talking about “UX Engineers”. It made me think more about the creativity of people inventing terms in areas in which they have no competence, rather than the post’s content itself.

If you’re a product designer looking for a job you may have come across the variety of job descriptions ranging from industrial designers to UX designers, and LinkedIn apparently concludes with its suggestions that “product manager”, “product owner”, “product consultant” and “product designer” are all one and the same.

I can relate to the perception that the increase of terms and names in the design and UX fields may not help with these fields being taken seriously. But I’d argue that a lot of this has to do with our own insecurities as professionals, trying to get jobs at companies who are insecure themselves about their needs and their requirements.

Most companies needing designers don’t even know yet why, or even the fact that they do need design. Most often, design is still seen as an afterthought, something to apply when the actual work is finished.

Many of the companies looking for designers have no actual concept of what they need from them, because by design, design is a process of learning, development and adaptation, not just an expected result to be executed.

A more coherent analysis of job diversity

I believe that between the artistic viewpoint and the concept viewpoint, there is a span of jobs with design tasks along that spectrum. And on the other side, between research and development, there are tasks aiming to learn, to inform us, to experiment and build upon that information, until we make progress.

If we put these two dimensions on a horizontal line and set them apart, we get a tension field in which design jobs find their spot. Some are leaning more towards the inspirational concept, so that’s more what graphic designers do. On the other side of the spectrum, product designers operate more with iterative cycles: they learn, build, check if what they built works and then introduce changes to optimise their product.

To get this out of the way: I’m not implying that illustrators and graphic designers cannot do their own research, say, to come up with a concept for a logo. It’s just not the same kind of work UX researchers do, when they’re conducting surveys and listening sessions to explore needs and expectations of potential users of a system.

This matrix may not be perfect, but it helped me to recognise the fundamental differences with expectation sets for each profession. Suddenly, User Centred Design and UX, or product design, or interaction design, do no longer seem one and the same.

Dynamics of organic evolution and classification

Putting design professions in one or the other corner of this matrix doesn’t negate how these job profiles came to be. Each term has its own history following a process of distinction, separating them from a more general description.

I expect the job landscape to continue to shift and adapt to changing requirements for any profession in the design fields. Given the current progress with LLMs and AIs, we can already foresee a wave of profound changes in the near future.

Botany today is not exactly what it was in Darwin’s times. The same is true for medicine and engineering. We learn, adjust, adapt and change. If we wouldn’t be able to do that as designers, we would fail our inherited mission, to connect what we see and improve it for people to have delightful and enjoyable experiences with it.

Call it UX or UCD or industrial, interior, graphic, type or product design — this mission is something we all share. Let’s rely on what makes our job unique, and we’ll continue to define meaning for it through our work.

This article was first published on my blog and on LinkedIn on January 23, 2024.